Thousands of Native Indigenous Women Disappeared / Murdered

in Canada and U.S.

Phenomenon

of Missing & Murdered Indigenous Women Has Become an Epidemic in the US

13:51 August 12, 2018

Native American women in the United States experience some

of the highest rates of sexual assault in the Nation: four out of five are

expected to encounter violence in their lifetimes; one

in three are raped in their lifetime; and the murder rates of Native

women exceed

ten times the national average in some tribal and urban communities.

US authorities gather missing person statistics for every demographic except

for Native American women. Although there is no accurate real-time data detailing

the rates of missing and murdered indigenous women, communities on and off

reservations maintain that the number is very high.

“It’s not a crime to be missing,” said

Warren Silver, an analyst with the Statistics Canada agency. In fact, such an

approach is rather common for both the United States and Canada and has proven

to be unable to keep track of violent crimes against indigenous women.

Violence against women is a growing concern in North

America, but no one seems to care. A flawed tribal court structure, little

local law enforcement, and a lack of funding fail to protect indigenous women.

They are more than TWICE as likely to face sexual-assault crimes as any other

ethnic group. According to the factsheet

presented by the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, among 10 to

24 year-olds, homicide is the third leading cause of death American Indians and

Alaska Natives. About 46% of Native American women have been raped, beaten, or

stalked by an intimate partner. As reported by Rewire.News, nearly every Native American family has a

story of a female relative who has gone missing or been murdered.

Although over the last year media support for indigenous

populations in the United States and Canada has grown, decades of

disproportionate murder and abduction rates among native women point to an unsettling

trend of underlying disdain against Native Americans.

“She’s probably just out drinking somewhere and afraid to

come home,” these were the words of a tribal police officer when Limberhand

first reported her daughter missing on the Northern Cheyenne Indian

Reservation. Unfortunately, it’s not the only case of such a devil-may-care

attitude among tribal authorities. In 2013, when Malinda Limberhand tried to

report her 21-year-old daughter Hanna Harris missing on the Northern Cheyenne

Reservation in Montana, tribal police dismissed her concerns insisting that

Harris was likely out drinking during the July 4th weekend. Both

girls were later found murdered. “Native women are often not seen as worthy

victims. We first have to prove our innocence, that we weren’t drunk or out

partying,” said

Carmen O’Leary, executive director of the Native Women’s Society of the Great

Plains. “We should never have a woman come into the office saying, ‘I need to

learn more about Plan B for when my daughter gets raped,’” said

Charon Asetoyer, a women’s health advocate on the

Yankton Sioux Reservation in South Dakota, referring to the morning-after pill.

“That’s what’s so frightening — that it’s more expected than unexpected. It has

become a norm for young women.”

A 2016 National Institute of Justice report

analyzing the findings of a 2010 study added momentum to the issue with data

about the high rates of violence against Native people. The report was the

first with specific data on the prevalence of homicide for women of all racial

and ethnic backgrounds, as well as the potential causes. Yet it only offered a

glimpse of the problem – between 2003 and 2014, just 18 states provided the

information needed to show how many Native women were murdered within their

borders.

According to the report, more than four in five American

Indian and Alaska Native women (84.3%) experience violence in their lifetimes.

Overall, more than 1.5 million American Indian and Alaska Native women have

experienced violence in their lifetime — 730,000 of them in 2015 alone.

Of intimate partner violence, 81.5% of Native victims were

murdered by a current partner while 12% were murdered by a past partner.

Arguments, jealousy and recent acts of violence preceded the homicide in

two-thirds of the incidents, according to the report. “Homicides occur in women

of all ages and among all races/ethnicities, but young, racial/ethnic minority

women are disproportionately affected,” the report stated. According to the

survey, 56% of 2,000 women surveyed have experienced sexual violence, over 90%

of that group has experienced violence at the hands of a non-tribal member.

The report also speaks to the nation’s indifference to the

dangerous forces that prey on indigenous women: few estimates are available to

describe the prevalence of violence against American Indian and Alaska Native

women and men. Moreover, these estimates are often based on local rather than

national samples.

Twitter

The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) released its own report on April 6, 2017.

What do conclusion do you think they came to? Right. The GAO said federal

agencies are “failing to collect data on Native trafficking victims”. As a

result, “it's not possible to determine the extent of the problem”. “In certain

circumstances, state or tribal law enforcement may have jurisdiction to

investigate crimes in Indian country; therefore, these figures likely do not

represent the total number of human trafficking-related cases in Indian

country,” the GAO wrote in the report. It added that of the four agencies with

investigative and prosecutorial powers in Indian Country, only the Bureau of

Indian Affairs collects data on the tribal affiliation of a trafficking victim.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Department of Homeland Security and

the network of U.S. Attorneys across the nation either fail to collect the same

information or only do so in limited circumstances, according to the report.Without a standing requirement to file national

level reports of violent crimes or abductions unless the victim is a juvenile,

many native women can simply go missing unnoticed.

Twitter

In July, 2017, the new report appeared.

That time it was the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) who

took up the challenge. “The racial/ethnic differences in female homicide

underscore the importance of targeting prevention and intervention efforts to

populations at disproportionately high risk," the report stated.

“Addressing violence will require an integrated response that considers the

influence of larger community and societal factors that make violence more

likely to occur.” The report only proved the facts that had already been known:

native women suffer from the second-highest homicide rate in the United States

after Non-Hispanic African Americans(4.4 and 4.3 per 100,000 population,

respectively). It also showed that most Native victims of homicide are young.

According to the data, 36.3 percent were between the ages of 18 and 29.

In the second report on the

issue conducted in July 2017, the GAO said only 27 of 132 tribal law

enforcement agencies (LEA) that responded to a survey initiated human

trafficking investigations between 2014 to 2016. Of 61 major city agencies, 6

started similar investigations. “Tribal and major city LEA respondents

indicated that unreported incidents and victims' reluctance to participate in

investigations are barriers to identifying and investigating human trafficking

in Indian country or of Native Americans,” the report stated.

While the U.S. authorities elaborated their reports, women

continued to go missing. June 5, 2017, was the last time friends or family of

Ashley Loring HeavyRunner recall seeing or hearing

from her. She seemed to disappear without a trace from the Blackfeet

Reservation near Browning, Glacier County, Montana. The details in her case are

scant. The FBI recently (in March 2018) began investigating her disappearance,

and the reward for information regarding her whereabouts has grown to $10,000,

but those missing her say the response has been too slow – too little, too

late. Officials confirm they have performed six searches and 60 interviews and

that they have unnamed persons of interest in the case. But as of today, Ashley

remains missing and her family still has no answers.

Ashley Loring HeavyRunner

went missing from the Blackfeet Reservation in Montana in June 2017

Her older sister Kimberly Loring thought of a promise she

once made.

“When we were young, we were in the foster care system,” she

told

ABC News. “She told me, ‘Don’t leave me,’ and I told her, ‘I would never

leave you, and if you were to get moved, I will find you.’”

“I don’t want to be an 80-year-old woman searching these

mountains with my grandchildren,” Kimberly Loring said. “But there’s no choice,

because if I give up, who’s going to look for her?”

Reddit

Following that case Annita Lucchesi, a doctoral student at the University of

Lethbridge in Canada, who used to teach Ashley Loring at the local community

college in Browning, Montana, set out to create her own database of missing and

murdered indigenous women by filing public record requests with local law

enforcement agencies. “After doing some Googling, I realized nobody has the

right number,” she said.

So far she has documented more than 2,000 cases across both the U.S. and Canada

the most of which occurred over the last 20 years. Lucchesi

says she's shocked at how much data is missing. “And really, it's not just

data,” she says. “That's someone's relative that's collecting dust somewhere

and no one is being held accountable to remember or honor the violence that was

perpetrated against her.”

In August, 2017, another disappearance occurred. That time

it was a 22-year old Savanna

LaFontaine-Greywind, a pregnant member of the

Spirit Lake Tribe who was tragically murdered. 5th October, 2017,

Rep. Norma J. Torres (D-CA) and Rep. Tom Cole (R-OK) introduced Savanna’s

Act, a bill named in honor of the woman. Senator Heidi Heitkamp (D-ND) called

for improved federal crime data collection and the creation of a standardized

protocol for responding to reports of missing and murdered Native women. “It’s

time to give a voice to these voiceless women,” said Heitkamp during a speech

from the Senate floor. “It’s time to bring their perpetrators to justice and

give a voice to the families who are struggling even today, sometimes decades

later, to understand how this can happen in America.” “Savanna’s death was an

incredible tragedy, and, unfortunately, one that happens way too often to

Native women,” Heitkamp said.

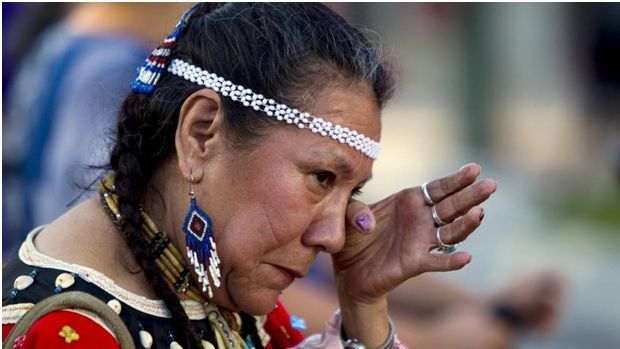

Several hundred people gathered for an

evening vigil for Savanna LaFontaine-Greywind at the

steps of the state Capitol in Bismarck on Aug. 30. Her death has prompted more

awareness about an epidemic of missing and murdered Native American women, with

Sen. Heidi Heitkamp introducing legislation in her honor. MIKE MCCLEARY, THE

BISMARCK TRIBUNE

It promised to be the first step in bringing about a

resolution to the issue with active engagement by the Federal government.

Unfortunately, nothing concerning the bill has occurred since its introduction.

Nevertheless, though late, some changes followed.

On January 20, 2018, in Seattle, Washington, 380 Native

women (and 3,200 interested onlookers) stated their intent on Facebook to join Missing & Murdered

Indigenous Women Washington (MMIW) by leading a Women’s March to call

attention to the epidemic of missing and murdered Native women in the United

States and Canada.

Roxanne White from the Missing and

Murdered Indigenous Women Washington leads the Woman’s March in Seattle Jan.

20. Photo by Matthew S. Browning.

People of all ages who supported the MMIW movement traveled

from all around to support the community of Indigenous families who have lost

family members. Some came from as far as Idaho, Nevada and Montana. “I’m here

for the entire movement and to raise awareness, because these women just

disappear off the face of the earth,” said

a woman from Beacon Hill. The attendees of the event, both Native and non, were

encouraged to wear red, the color that represents the MMIW movement.

Soon after that, on January 29, 2018, Representatives Gina

McCabe, Mia Gregerson, Melanie Stambaugh, Derek Stanford,

Kristine Reeves, Mary Dye, Andrew Barkis, and Senator

Maureen Walsh introduced HB-2951,

to do something about the situation. HB-2951 requires that “the Washington

state patrol must conduct a study to determine how to increase state criminal

justice protective and investigative resources for reporting and identifying

missing Native American women in the state.”

“There’s currently no comprehensive data collection system

for reporting or tracking missing Native American women,” McCabe told. “That’s

a travesty, and I know Washington can do better.” “By

December 1, 2018, the state patrol must report to the legislature on the

results of the study, including data and analysis of the number of missing

Native American women in the state, identification of barriers in providing

state resources to address the issue, and recommendations, including any

proposed legislation that may be needed to address the problem.” The bill also

tasks the Washington State Patrol with creating a list of missing Native

American women in the state by June 2019, by working with tribal and non-tribal

police agencies around the state.

“The place to start is by bringing the federal, state

and federally recognized sovereign tribal governments together to ensure that

everyone who goes missing is reported and listed in a central location,” McCabe

said.

“There seems like there’s this disconnect between local police and county

police and tribal police and the FBI,” McCabe says. “My goal is to get everyone

at the table.” Meanwhile, it is still vital for Native activists to continue to

speak about this issue and keep pressure on Washington’s legislatures. And they

definitely will.

While lawmakers consider changes at the law enforcement

level, activists continue to push the issue at the local and, potentially, the

national level. MMIW and other indigenous activists have been organizing

protests and vigils for many years. The Women’s Memorial March takes place

annually on Valentine’s Day in more than 22 communities across North America.

In 2018 the action took place in Minneapolis, on February 13, 2018, hundreds

gathered at the Minnesota Indian Women’s Resource Center to participate in an

art build for the February 14th day of action for MMIW.

They also started the “Longest

Walk” on February 16th in Blaine, Washington, making stops in

Eastern Washington on their way to the capitol. “We need to stand united on all

the issues Native Americans and America faces today. To do so we must have a

strong society. Standing

Rock proved we can come together to aid to each other. We must continue in

that same spirit and halt the flow of drugs and violence into our communities

to remain strong. Along the route we will help clean up Mother Earth. Victory

shall dwell in the house of unity, to those that follow that spirit,” these are

the words pronounced

at the Opening Ceremony at Peach State Park, Blaine, WA.

“So many people don't understand that we do still struggle

with colonization and domestic violence, and it's a topic that nobody wants to

talk about,” Niki Zacherle, a member of the

Confederated Colville Tribes, says.

longestwalk.us

Facebook

Yet another Indigenous woman has gone

missing in the Mountain West. Jermaine Charlo disappeared near a grocery

store in Missoula, Montana. On June 15th, 23-year-old Jermaine Austin Charlo

disappeared from the Missoula area and has not been seen since. Missoula Police

Detective Guy Baker said that law enforcement agencies are now taking the extra

step of reaching out to the public for help in finding the missing young woman.

The 23-year-old is the 13th native woman to go missing in the state since

January.

Courtesy of the Missoula Police

Department

Reddit

Do YOU want to help? Here’s how:

Encourage your legislators to support Savannah’s

Act.

Support the Red

Ribbon Alert project. This project offers an alert system for

when a Native American woman goes missing. Like their

Facebook page and share missing women alerts from your area.

Get to know the tribes near you. Start by learning

about them, then follow the social media accounts of local tribes to find

out about what’s happening in their communities. Attend public events and get

to know people.

Learn about domestic violence and support organizations that

support victims. The National

Domestic Violence Hotline launched the StrongHearts Native Helpline specifically for

indigenous populations, they offer helpful information about

supporting all domestic violence victims. You can also donate to the

hotline here.

Author: Christine Petrova

Dozens

of Women Vanish on Canada’s Highway of Tears, and Most Cases Are Unsolved

A billboard along Highway 16. The

stretch of road is known as the Highway of Tears because dozens of women, mostly

aboriginal, have been murdered or have disappeared in the area.CreditRuth

Fremson/The New York Times

Image

A billboard along Highway 16. The

stretch of road is known as the Highway of Tears because dozens of women,

mostly aboriginal, have been murdered or have disappeared in the area.CreditCreditRuth Fremson/The

New York Times

New York Times By Dan Levin

- May

24, 2016

SMITHERS, British Columbia — Less than a year after her 15-year-old

cousin vanished, Delphine Nikal, 16, was last seen

hitchhiking from this isolated northern Canadian town on a spring morning in

1990.

Ramona Wilson, 16, a member of her high school baseball

team, left home one Saturday night in June 1994 to attend a dance a few towns

away. She never arrived. Her remains were found 10 months later near the local

airport.

Tamara Chipman, 22, disappeared in 2005, leaving behind a

toddler. “She’s still missing,” Gladys Radek, her aunt, said. “It’ll be 11

years in September.”

Dozens of Canadian women and girls, most of them indigenous,

have disappeared or been murdered near Highway 16, a remote ribbon of asphalt

that bisects British Columbia and snakes past thick forests, logging towns and

impoverished Indian reserves on its way to the Pacific Ocean. So many women and

girls have vanished or turned up dead along one stretch of the road that

residents call it the Highway of Tears.

The sparsely populated landscape along

the highway.CreditRuth Fremson/The

New York Times

Image

The sparsely populated landscape along

the highway.CreditRuth Fremson/The

New York Times

A special unit formed by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police

officially linked 18 such cases from 1969 to 2006 to this part of the highway

and two connecting arteries. More women have vanished since then, and community

activists and relatives of the missing say they believe the total is closer to

50. Almost all the cases remain unsolved.

The Highway of Tears and the disappearances of the

indigenous women have become a political scandal in British Columbia. But those

cases are just a small fraction of the number who have been murdered or

disappeared nationwide. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police have officially

counted about 1,200 cases over the past three decades, but research by the Native Women’s Association of Canada

suggests the total number could be as high as 4,000.

You have 2 free articles

remaining.

In December, after years of refusal by his conservative predecessor,

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced a long-awaited national inquiry into

the disappearances and murders of indigenous women.

The inquiry, set to cost 40 million Canadian dollars ($31

million), is part of Mr. Trudeau’s promise of a “total renewal” of Canada’s

relationship with its indigenous citizens, and it comes at a critical time.

Aboriginal women and girls make up about 4 percent of the

total female population of Canada but 16 percent of all female homicides,

according to government statistics.

Carolyn

Bennett, the minister of indigenous and northern affairs, has spent months

traveling across the country to consult with indigenous communities. During her

meetings, families and survivors have complained of racism and sexism by the

police, who she said treated the deaths of indigenous women “as inevitable, as

if their lives mattered less.”

“What’s clear is the uneven application of justice,” Ms.

Bennett said.

One reason to doubt the estimate by the Royal Canadian

Mounted Police, she said, is that the police often immediately deemed the

women’s deaths to be suicides, drug overdoses or accidents, over the protests

of relatives who suspected foul play. “There was no investigation,” she said,

citing one recent case. “The file folder’s empty.”

A United Nations report last year described measures by the

previous government to protect aboriginal women from harm as “inadequate” and

said that the lack of an inquiry into the murders and disappearances

constituted “grave violations” of the women’s human rights. Failures by law

enforcement, it added, had “resulted in impunity.”

Ms. Radek, a co-founder of Tears4Justice, an advocacy

organization, said, “When it comes to the missing, racism runs deep.”

The federal government has allocated 8.4 billion Canadian

dollars ($6.4 billion) over five years to aid indigenous communities, which

have disproportionately high levels of poverty, incarceration, alcoholism and

substance abuse, and often lack basic necessities like safe drinking water.

Drucella Joseph and her boyfriend, Corey Coombes, waiting along

Highway 16 near Houston, British Columbia, in hopes of catching a ride.CreditRuth Fremson/The New

York Times

Image

Drucella Joseph and her boyfriend, Corey Coombes, waiting along

Highway 16 near Houston, British Columbia, in hopes of catching a ride.CreditRuth Fremson/The New

York Times

Ms. Bennett said the breakdown in aboriginal communities was

the product of generations of socioeconomic marginalization and trauma tied to

government policies. Particularly damaging was a

state-financed, church-run boarding school system for aboriginal children

who were forcibly taken from their families by officers of the Royal Canadian

Mounted Police. Many of the 150,000 children who were sent to residential

schools over a century became victims of physical and sexual abuse. The program

was fully shut down in the mid-1990s.

Covering 450 miles between the city of Prince George and the

Pacific port of Prince Rupert, the Highway of Tears is both a microcosm of

Canada’s painful indigenous legacy and a serious test for Mr. Trudeau as he

tries to repair the country’s relationship with aboriginal people.

On a recent journey along Highway 16, scenes of stunning

wilderness were flecked by indigenous communities reeling from economic decay

and the anguished memories of missing and murdered women.

A few miles outside Prince George, the highway plunges into

thick forests veined with logging roads and the occasional “moose crossing”

sign. “Girls Don’t Hitchhike on the Highway of Tears,” reads a large yellow

billboard alongside the road farther north. “Killer on the Loose!”

As a bald eagle soared overhead, Brenda Wilson, 49, the Highway

of Tears coordinator for Carrier

Sekani Family Services and the sister of one of

the victims, gestured to the wall of evergreens that flank the road. “The trees

are really dense here, so if you’re looking for someone, it’s pretty hard to

find them,” she said, listing the names of several women who are still missing.

Matilda Wilson wiping leaves off her

daughter’s gravestone at a cemetery in Smithers, British Columbia. Her

daughter, Ramona, 16, disappeared in 1994, and her body was found 10 months later.CreditRuth Fremson/The New

York Times

Image

Matilda Wilson wiping leaves off her

daughter’s gravestone at a cemetery in Smithers, British Columbia. Her

daughter, Ramona, 16, disappeared in 1994, and her body was found 10 months later.CreditRuth Fremson/The New

York Times

The provincial government announced plans in December to

improve safety along Highway 16, including funds for traffic cameras and

vehicles for indigenous communities. But little has changed on the road, which

lacks lighting or any public transportation other than infrequent Greyhound bus

service that does not reach remote communities.

The perils do not stop desperate people from thumbing rides in

a region where public transportation is practically nonexistent. Just outside

the village of Burns Lake, Drucella Joseph, 25, an

unemployed aboriginal woman, eagerly climbed into the back of a passing car

along with her boyfriend, Corey Coombes. “Friends will drive me when I really

need a ride, but other than that, we just hitchhike,” she told the driver. The

couple gets by on his disability payments and on donated food from food banks.

Neither has a cellphone. When hitchhiking, Mr. Coombes says he protects himself

by carrying a club or a screwdriver.

British Columbia is infamous for serial killers and

criminals who often targeted aboriginal women. In 2007, Robert

William Pickton, a pig farmer, was convicted of

killing six women, though the DNA or remains of 33 women were discovered on his

land. Many of them were aboriginal. One of Canada’s youngest serial killers, Cody Legebokoff, was 24 when he

was convicted in 2014 of killing four women near the Highway of Tears. David Ramsay, a former Prince George provincial court judge

and convicted pedophile, was imprisoned in 2004 for sexually and physically

assaulting indigenous girls as young as 12.

Anguished family members said they received little help from

the authorities, a sharp contrast to the cases of missing white women. After

Ms. Chipman vanished in 2005, her aunt, Ms. Radek, said the police objected to

the family putting up its own missing posters. “They knew we were searching day

and night, and they did nothing to help us,” she said. The next day, she said,

a white woman disappeared near Vancouver “and the police were out in the

streets putting up posters.”

After her daughter Ramona disappeared in 1994, the police

refused to act, said Matilda Wilson, a member of the Gitxsan First Nation.

“They gave us all these different excuses that she might be back tomorrow or

next week,” Ms. Wilson said. “There was no hurry or alarm about it, so we started

looking ourselves.”

From left, Eryn Joseph, Rochelle

Joseph, Tiniel Namox and

Tricia Joseph near Highway 16 in Moricetown, British

Columbia. The women grew up hearing about the victims.CreditRuth

Fremson/The New York Times

Image

From left, Eryn Joseph, Rochelle

Joseph, Tiniel Namox and

Tricia Joseph near Highway 16 in Moricetown, British

Columbia. The women grew up hearing about the victims.CreditRuth

Fremson/The New York Times

Despite multiple searches, Ms. Wilson, a single mother of

six who is now 65, said there was no sign of Ramona until she had been gone for

seven months, when Ms. Wilson received an anonymous phone call telling her that

the girl’s body was near the airport. Police officers searched the area but

found nothing, she said. In April 1995, two men riding all-terrain vehicles by

the airport discovered Ramona’s remains buried under some trees. Plastic

flowers and a glass cross now decorate her grave in a Smithers cemetery, a few

blocks from Ms. Wilson’s tidy trailer-park home.

Angry with the police for failing to find the teenager or to

alert people to the history of missing women near Highway 16, Ms. Wilson and

her family organized a memorial walk in June 1995 that has become an annual

event, garnering attention from the news media and inspiring activism from

families of other missing women.

“We want closure, and we’re not going to give up,” Ms.

Wilson said as she swept leaves from her daughter’s gravestone.

One recent afternoon, three young aboriginal sisters and

their female cousin were walking across the Moricetown

Indian Reserve, which abuts the highway. Asked about the Highway of Tears, one

of the women, Rochelle Joseph, an unemployed 21-year-old, said the sisters

never hitchhiked because they grew up hearing about the victims, including their

cousin, Ms. Chipman.

Still, the menace of the highway haunts their lives.

“The stories made us cautious,” Ms. Joseph said quietly,

voicing their fear of a serial killer lurking behind the steering wheel of any

strange car. “He’s probably still out there.”

Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women in the United States

https://medium.com/@aperez14/murdered-and-missing-indigenous-women...

The map shows points that visualize

murdered and missing indigenous women in the United States,

hover over and click on each point for more information regarding the victims.

The mystery of 1,000 missing and murdered indigenous women

...

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2016/08/04/the...

Posters of missing women hang at a Vancouver

shop in 2001. (DeNeen L. Brown/The Washington Post)

OTTAWA — They call it the Highway of Tears, a 450-mile stretch of the

Trans-Canada Highway through northern British Columbia where at least 18 young

women have disappeared or been murdered since 1969. Half of them were indigenous.

Phenomenon of Missing & Murdered Indigenous Women Has

...

https://usareally.com/1052-phenomenon-of-missing-and-murdered...

On January 20, 2018, in Seattle, Washington,

380 Native women (and 3,200 interested onlookers) stated their

intent on Facebook to join Missing & Murdered Indigenous

Women Washington (MMIW) by leading a Women’s

March to call attention to the epidemic of missing and

murdered Native women in the United States

and Canada.

Missing and murdered Indigenous women - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Missing_and_Murdered_Indigenous_Women

Sisters in Spirit Vigils. The annual Fort St.

John, British Columbia vigil has been taking

place since 2008, honouring missing

and murdered Indigenous women and girls in northeast British Columbia.

Sisters in Spirit continue to hold an annual, national vigil on Parliament Hill

in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

Missing & Murdered Indigenous Women: Resources ...

https://www.heitkamp.senate.gov/public/index.cfm?p=missing...

Missing & Murdered Indigenous Women:

Resources & Information. Across rural North Dakota, women

living on reservations face unique challenges when dealing with

violence. Access to telephones, transportation, emergency services, law

enforcement officers and confidential victim services all act as barriers to

getting the help they desperately need.

Missing and Murdered Native Women | National Indigenous ...

www.niwrc.org/resource-topic/missing-and-murdered-native-women

Honoring Missing and

Murdered Indigenous Women. One of the findings of this title

was that during the period of 1979 through 1992, homicide was the third-leading

cause of death of Indian females aged 15 to 34, and 75 percent

were killed by family members or acquaintances. Since that

time, a study by the U.S.

Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women USA - Home | Facebook

https://www.facebook.com/mmiwusa

Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women USA.

18,927 likes · 7,141 talking about this. This page is dedicated to helping missing

and murdered American...

- 4.8/5

(53)

Missing and

Murdered Indigenous Women USA - Posts | Facebook

https://www.facebook.com/mmiwusa/posts

Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women USA

added 4 new photos. December 13, 2018 · ***JOAQUIN IS MISSING

OUT OF PORTLAND, OREGON BUT COULD HAVE BEEN TRAFFICKED BY A WHITE MALE NAMED

MICHAEL.

- 4.9/5

(55)

- missing

native american women database

- missing

and murdered indigenous women

- how

many native american women are

missing

- missing

native american women pictures

- missing

native women in montana

- missing

and murdered indigenous women usa

- missing

native american women

- missing

or murdered native women

- missing

indigenous women canada

- canadian indigenous

women missing

- indigenous

missing women

- indigenous

women in canada

- missing

indigenous women usa

- missing

indigenous women in montana

- missing

indigenous peoples

- missing

& murdered indigenous women

· missing

indigenous women canada highway 16